I recently used a memory system to help me memorize a few passages of text which I love. I began with one of my favorite pieces of writing, Carl Sagan's famous "Pale Blue Dot". I found the experience rewarding enough that I memorized several more passages, including Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address; and Wendell Berry's poem "The Peace of Wild Things".

These notes collect a few observations on my experience. They're just my personal notes – I'm certainly not claiming this is something anyone "should" be doing, or that the process I used is the best, or even particularly good. I know many people are much better than I am at this kind of memorization, and no doubt have useful techniques of which I'm ignorant1. That said, perhaps the notes will be of use to a curious few, and inspire related explorations.

I shall assume that you're familiar with the use of memory systems. I use Anki – there are many similar memory systems, which I assume would work about as well2. I've written extensively about my use of memory systems: here is an introduction if you're new to memory systems. As I wrote there, memory systems "make memory a choice", i.e., rather than leaving to chance whether or not you remember something, you can make it so you have near certainty; you simply decide you will remember something, and the system ensures it will happen. In some sense the purpose of the current notes is to investigate whether that sense of memory as a choice can be extended to entire passages of text. The answer is a qualified "yes". The qualification is for two reasons. First, and most practically, I'm only a month or so into this experiment: it remains to be seen how fluent I am in a year or five years. Second, the memory system has played a different role than I initially anticipated. As we'll see, while it has certainly helped with memorization, it's not quite as decisive as in more conventional uses of memory systems. Its role has instead been to help me deepen my understanding of the passage; at that, it has been outstanding.

For later reference, let me quote in full the three passages I've memorized – the Pale Blue Dot, the Gettysburg Address, and the Peace of Wild Things. You can, if you like, skim over one or all three passages, though I think all three are so beautiful and stimulating that they're worth reading carefully. Of course, I wouldn't have spent the time to memorize them if I thought otherwise!

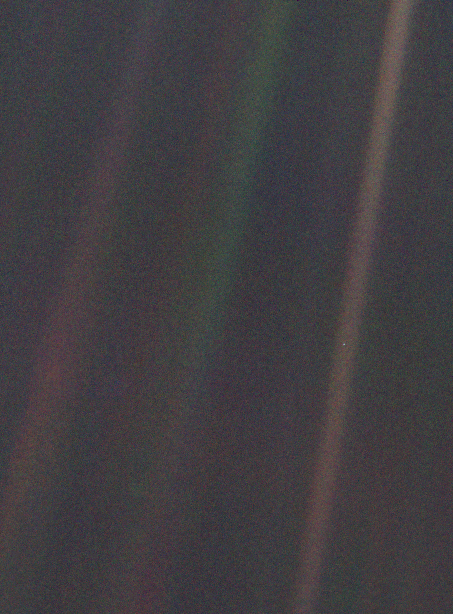

For the Pale Blue Dot, helpful context is that Carl Sagan is talking about a famous image of Earth taken by the Voyager spacecraft – so far away the Earth appears a tiny dot in the image:

Here's the passage:

From this distant vantage point, the Earth might not seem of any particular interest.

But for us, it’s different. Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every “superstar,” every “supreme leader,” every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there—on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that, in glory and triumph, they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner, how frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds.

Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the Universe, are challenged by this point of pale light. Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.

The Earth is the only world known so far to harbor life. There is nowhere else, at least in the near future, to which our species could migrate. Visit, yes. Settle, not yet. Like it or not, for the moment the Earth is where we make our stand.

It has been said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience. There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.

Here's the Gettysburg Address. This passage exists in several different version. I used the "Bliss" version, which is perhaps the best known, appearing at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington:

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate – we can not consecrate – we can not hallow – this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us – that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion – that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain – that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom – and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

And, finally, Wendell Berry's poem "The Peace of Wild Things":

When despair for the world grows in me and I wake in the night at the least sound in fear of what my life and my children’s lives may be, I go and lie down where the wood drake rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds. I come into the peace of wild things who do not tax their lives with forethought of grief. I come into the presence of still water. And I feel above me the day-blind stars waiting with their light. For a time I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.

Let me make a few background observations on the process I used. In the next section I'll discuss the big picture.

Don't use willy-nilly prompt-continuation cloze deletions: I made many mistakes in how I approached this. My initial approach, perhaps the simplest thing one might try, was to use cloze deletions in a kind of prompt-continuation format. For instance, I'd have a cloze like: "Q: Look again at that dot. _. _. _.", with answer: "A: That's here. That's home. That's us." Or sometimes, for complex sentences, I'd use individual phrases: "Q: Everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, _, _"; "A: every human being who ever was, lived out their lives".

You could mechanically convert the entire Pale Blue Dot passage in this way: each Anki card would be a prompt phrase or sentence, with the answer being one or more completion phrases or sentences. It's simple and natural, and my experiments suggest it would certainly work. But that said: it was an unsatisfying and slow grind. Part of the issue was that when I got a question wrong during review, I was often just a little vague in my own mind about what exactly I'd gotten wrong. Of course, if I'd been more disciplined I would have said aloud the exact mistake I'd made. But in practice that didn't always happen, and so the feedback effect was weak. I find memory system questions work best when they're extremely sharp – often short and atomic – so that when you miss a question it's extremely clear what you missed. That sharp feedback helps you learn rapidly. With long, complex clozes there's just too many ways things can go wrong.

This suggests trying very short cloze deletions instead, e.g.: "Q: Look again at that dot. _"; "A: That's here." This has the virtue that you get very sharp feedback. But it was also a mistake. It was a bit like trying to grok a Picasso by studying 3 by 3 patches of pixels. It resulted in a big pile of questions, most of which alienated me from passages of writing I love. So while the mechanical cloze deletion approach was tempting, I eventually realized it was much better to use clozes only for very limited and targeted reasons (of which many examples below).

Basic principle: look for questions which (a) make for good Anki cards, and (b) do the most to deepen your understanding of the passage: This was the most useful general principle I found, and nearly all the examples I give through these notes are instances. Let me give three immediate examples. In the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln says it's about dedicating a portion of the battlefield "as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live". It's notable that here, as throughout the speech, he never distinguishes between soldiers of the North and of the South. I added several questions reflecting on this, e.g.:

"Q: In the Gettysburg Address, Lincoln doesn't directly distinguish between soldiers of the North and the South. He asserts that all 'gave their lives that [the United States] might live'. Did the soldiers of the South think they were doing this?"; "A: Almost certainly not.".

This card expresses a useful insight. It's inadequate, in that I prefer to avoid Anki cards with yes-or-no answers, or (worse still) weasel-word variants3 like "Almost certainly not". I find I don't engage deeply enough with such questions when I review. In general, the more specific and meaningful the question and the more specific and meaningful the answer, the better an Anki card will be. When I do add yes-no type cards, I make it a rule to add at least one (and often several) more deeply engaging question (or questions). For instance, in this case4:

"Q: The soldiers of the South probably didn't think they were giving 'their lives that [the United States] may live'. In what larger sense was Lincoln correct when he implied that they were?"; "A: That seems likely the meaning Lincoln personally saw for their sacrifice, and which he was trying to will into the way others saw it."

As a second example, in the Pale Blue Dot Sagan writes "Thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines." Many things about this fragment bother me. Initially, "economic doctrines" seemed out of place, especially compared to "religions" – while opponents sometimes charge that capitalism or communism are religions, these tend to be rather shallow charges. I wondered if Sagan was making some deeper point that I had missed. Upon reflection one commonality struck me as particularly worthy of note: human beings have a lot of agency over all three, even though it sometimes may seem otherwise. And so I added the Anki card:

"Q: What's an important commonality between 'Thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines'?"; "A: We get to choose all three, they are matters of human agency."

This line of questioning also made me wonder if "economic systems" might not be better than "economic doctrines"? And so I added:

"Q: How would I improve 'economic doctrines' in 'Thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines'?"; "A: economic systems".

"Q: Why do I think 'economic systems' is better than 'economic doctrines'?"; for this card I left the answer blank, since this is something I want to reflect upon each time. It doesn't necessarily have a fixed answer. Indeed, I'm not even sure I will continue to believe this! Right now, my answer is something like: the actual (rather than notional idealized) economic system is really the more fundamental thing in our lives.

That said, when I recite the passage I don't modify Sagan's text to say "economic systems". But the thought will often flit across my mind: "This would be a little better with 'economic systems' here." And I find that thought makes it easier to remember the Pale Blue Dot. There's a little frisson as I say Sagan's words, but secretly think "'systems' would be better!" Of course, you might disagree! Maybe you think "economic doctrines" is better. Maybe you like the resonance between "doctrine" and "religion". That's fine – indeed, it'd likely make for some good Anki cards. But personally I prefer "economic systems".

Understanding non-obvious choices: All the passages I memorized make many choices which I didn't find obvious at first. Often deeper reflection revealed benefits:

"Q: What's a benefit of Sagan using 'rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors' over 'emperors and generals'?"

"A: It goes from a specific concrete cause [generals] to a more abstract cause [emperors and state power]"

One can riff on this:

"Q: How does Sagan's reference to 'rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors' connect to the modern day?"

"A: The archaic use of emperors implicitly asks us to ponder to what extent this is also true of modern governments"

As another example, in the Pale Blue Dot I'd sometimes mistakenly recall: "To me it underscores the need to deal more kindly with one another", when Sagan uses "responsibility" instead of "need". Of course, "need" has some benefits: it's a shorter, simpler word, and carries almost the same weight of meaning. I reflected upon the merits of both choices, and added the following:

"Q: What is a benefit of 'To me it underscores the responsibility to deal more kindly with one another' over 'To me it underscores the need to deal more kindly with one another'? A: I left it blank, as a challenge to re-engage with the question each time.

Such questions about individual words may appear to be pedantic nitpicking. Does it really matter whether one uses 'need' or 'responsibility'? In individual cases the answer is often "not much". But in aggregate I believe it matters a lot, especially in great writing, where there is deep and considered meaning in every word. There is often a lot going on in those word choices that is not immediately obvious to even a well informed reader. By trying to understand the reasons for the choices you start to better understand what the author was thinking. Furthermore, in practice I found questions about single words made them much easier to remember.

Using mistakes as a source of insight: As the previous example suggests, every time I made a mistake in recitation, or even just encountered a difficulty, it invited me to ask: did I understand this well enough? What was I missing? It was usually not a failure of memory so much as a failure to understand as well as the author. For example, in testing myself on the Pale Blue Dot, I sometimes used the phrase "the aggregate of their joy and suffering", when Sagan uses "our" in place of "their". Sagan's choice is much better – it connects us more to a shared human sense of the passage. So I added an Anki question:

"Q: 'the aggregate of _ joy and suffering': why is 'our' better than 'their'?"

"A: He is talking about humanity, and the use of 'our' connects us to our shared humanity"

In general, synonyms cause many problems of this type. Consider the Gettysburg Address, and its reference to testing whether any nation so conceived and so dedicated "can long endure". This would be a little shorter as "can long last". Usually, I'd prefer the shorter text. But upon reflection, "long endure" is better than "long last". It puts the emphasis more on "endure", which is where the listener's attention belongs. Again: it's easy to construct Anki questions about this.

These are superbly constructed texts, and it is perhaps not surprising that I found many instances where the author made a better choice than my initial instinct. A lovely consequence was that as I understood those choices, I found recitations of the passage becoming a richer and richer experience, a chance to appreciate in real time many of the beautiful choices that had been made.

As I did this I came to think of the entire process as not really being about memorizing the text at all. It was about gradually deepening my understanding of the thinking behind the text. Great texts aren't just strings of words. They emerge out of and express an extraordinary depth of understanding. What you're trying to do isn't really to memorize the text so much as to understand what it was Lincoln understood, what Sagan understood, and so on. Why did they write what they wrote? In this view, memorization is merely a way to force oneself to understand more deeply the thinking that led to the text, and to test that understanding. Put another way, what it was really about was internalizing a point of view in which the text is simple and natural, just the kind of thing you'd "naturally" want to say.

The title and framing for these notes emphasizes memorization. That's the way I approached this project initially. But in some sense it's the wrong framing: it's really about how to understand great texts much more deeply. So the title and framing now bothers me: it'd perhaps be better as "Using memory systems to metabolize text passages". Still, these are notes, a partial and (largely) along-the-way record of what I did. Perhaps one day I'll rewrite with the benefit of hindsight!

Improvements: Another way of deepening my understanding of a passage was to find improvements. For instance, Sagan writes: "There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world." It's a good sentence, but I think "illustration" is clearly better than "demonstration". And so again I added a couple of questions:

"Q: How can we improve Sagan's sentence: 'There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world'?"

"A: There is perhaps no better illustration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world."

"Q: Why is 'illustration' better than 'demonstration' in Sagan's sentence: 'There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world'?"

"A: 'demonstration' often implies a demonstrator, but of course there is no agency intended here"

Because these are such well written passages it's not so easy to find improvements! Most of the improvements I found were minor. Still, I found it useful and fun to spend time looking for such improvements. There is a pleasurable frisson as you recite the passage, and secretly you're thinking of some way of making it better! Again: it's a way of changing and deepening your relationship to the text.

Doing this also gave me more insight into how well a text was (or was not) constructed. I found it challenging to improve "The Pale Blue Dot" and "The Peace of Wild Things". By contrast, while the Gettysburg Address is an extraordinary piece of writing, I found it relatively easy to find improvements. I've come to think of it as expressing extremely powerful ideas, which Lincoln had reflected upon for many years, but where the actual text was (perhaps) composed somewhat hurriedly. By contrast, I found it difficult to improve "The Peace of Wild Things" – the main point of weakness is the line "And I feel above me the day-blind stars waiting with their light". I also found Berry's poem to be, word-for-word, the easiest to memorize. I suspect that the better written a text is the easier it is to remember: every word is extremely well chosen, and carries great weight of meaning, forming part of a tight, almost perfect spoken thought.

Exert special effort on the beginning: I found the beginnings of the passages surprisingly difficult, and expended quite a bit of effort, constructing many questions:

"Q: What is the first word of the Pale Blue Dot passage?"

"A: From"

"Q: What is the first phrase of the Pale Blue Dot passage?"

"A: From this distant vantage point…"

"Q: What should you imagine you are looking at when the Pale Blue Dot passage begins?"

"A: [the image shown earlier in these notes, which I won't repeat here]"

"Q: What is the first sentence of the Pale Blue Dot passage?"

"A: From this distant vantage point the Earth might not seem of any particular interest."

Of course, sometimes the beginning of a passage is so famous that there's no problem. With the Gettysburg Address I've heard "Four score and seven years ago…" so often that it didn't need any work. The remainder of the first sentence did benefit from thorough analysis and reflection. I added questions about the gendered nature of "fathers" (I'd guess today we'd use "forebears" or something similar); about the redundancy of "on this continent"; about interesting verb choices ("conceived" and "dedicated"); about Lincoln's use of mathematical language ("the proposition"); and the particular facets of America's founding that he chose to emphasize (liberty, especially the idea that all men are created equal), and how they were apposite to the issue of slavery. I haven't counted, but in total I have perhaps a dozen questions about the opening sentence.

Let's come back to the Pale Blue Dot, and let me mention another question arising from uncertainty about word choice5:

"Q: Is there a reason to prefer 'might' over 'may' in 'From this distant vantage point the Earth might not seem of any particular interest'?"

"A: This would be fine to let pass. But 'might' is perhaps slightly more understated and distant, which matches the later tone Sagan uses."

In general, for things like this I give myself a pass on getting it "right" or not. What is important is arriving at a sense that I am not just fluent, but have absorbed much of the understanding behind the passage. When I start to feel that strongly, I no longer worry so much about minor deviations, although I still do note them as a source of curiosity and further insight. Speaking of which:

Let punctuation pass: I don't worry about getting the punctuation 'right' at all. Indeed, you can perhaps see that in various mismatches between the original passages and my Anki questions and answers above. Ultimately, punctuation is just not a level of meaning I care much about. Indeed, insofar as the goal isn't to be a recording device, but rather to metabolize the passage so that is useful in my own thinking, it helps to find ways of expressing agency. Making one's own choice of pacing and punctuation and phrasing is one way of doing that.

High-level observations: Over time I gradually added more and more high-level observations, often from multiple points of view. Let me give some examples:

Q: What does "The Pale Blue Dot" passage assume you're looking at?

A: The image of the pale blue dot!

Q: Why do I think Lincoln must have been somewhat rushed when composing the Gettysburg Address?

A: The later parts of the speech seem (mostly) much less well structured than the earlier parts, and have more inelegant phrasing.

Q: What's an example of the way in which the second half of the Gettysburg Address seems rushed?

A: The inelegant repetition of "rather" and "devotion", and several easily-eliminated words and phrases.

Q: Note the three-part structure of "The Peace of Wild Things", describing: (1) a difficult feeling faced by the author; (2) an action in response to that feeling; (3) the consequences of that action ("I rest in the grace of the world, and am free").

A: [None, this is just a card to inspire reflection]

Adding such high-level questions is, of course, an open-ended task. It is founded in curiosity, in believing that there is a great deal that can be discovered in the author's thinking. I've only talked about this briefly here, but it was perhaps the most rewarding part of this entire process.

I've been describing various details of the process of memorization. Now I want to zoom out and talk about the overall process. Note that I've described this linearly: in practice, I jumped back and forth. Furthermore, this wasn't (quite) the process I used for the first passage I memorized ("The Pale Blue Dot"). Rather, it's what I gradually evolved over multiple passages.

The process didn't end there. So far, I've found my understanding never saturates, no matter how many times I retest; I continue changing my relationship to the text passage. One striking thing has been the sense of passing through multiple stages: first getting to the point where I wasn't making mistakes; then to fluency; then to feeling like I was inside the text, where certain emotions and perceptions of the world were bubbling up. These were gradually expressed more and more fully in my intonation, in my body language, in my pacing, in my actual experience. As mentioned earlier, I started to feel that I'd gotten inside the text, to the point where I simply wanted to say this stuff. There was a sense of communion with the text, a state of consciousness where the writing seemed simultaneously chosen and inevitable. In this point of view, the questions in the memory system are almost a kind of scaffolding, a type of discovery fiction aimed at discovering and internalizing the emotional and mental unity underlying the text.

Through all this, it was important to delay as long as possible the moment at which I started to get bored with the text. The way to do that seems to be to keep pushing to find deeper and deeper meaning. I didn't always succeed! Sometimes I did find myself just reciting-on-automatic, disengaged. I've been doing all this as a private project; I suspect that more demanding public tests would push me to much more deeply understand a passage6. I'll bet that giving a public on-stage performance would be far more demanding than merely reciting while I'm out on my own on a walk.

To illustrate what I mean, think of great monologues from film history – say, Jack Nicholson's famous "You can't handle the truth" speech from "A Few Good Men". It's beautifully written by Aaron Sorkin. But Nicholson must have gone very deeply inside the writing, to understand what state of mind and emotions the (fictional!) character saying those lines must have been feeling, how he saw the world. "Perform this as the crucial monologue in a big budget film" is an extraordinarily demanding test!

(Tangentially, one very common piece of advice for people called upon to speak publicly is that they shouldn't memorize their text, but rather extemporize from an outline. Memorized text will, we are told, come out rather wooden and stilted. Empirically, I've certainly seen this happen with neophyte speakers. But I nonetheless think the advice is given for deeply mistaken reasons. There is a reason the best acting performances come from actors with scripts. They don't merely memorize those scripts, they metabolize them, internalizing and even discovering a kind of emotional reality, which they then express in their performance. Of course, this requires a very good script, and then tremendous effort to metabolize it. That's a lot of work, but is what results in the very best performances of all!)

This all sounds like a lot. It is a lot. I haven't kept statistics, but it took me a few hours to memorize the 400 words of "The Pale Blue Dot". Now, as mentioned, I expect there would be continued benefits to further investment of time, so time-to-memorization is in any case rather ambiguous. Further occluding the issue, although the time investment is large, understanding has very nonlinear returns. The mathematician Littlewood remarked in his memoirs that as he got older he decided only to listen to the music of Bach, Beethoven, and Mozart. I can see why: it's better to return again and again to something of extraordinary depth than to squander it on many things of far less merit. I consider my time with Sagan, Lincoln, and Berry, time well spent. I also suspect I would get faster at doing this upon repeated iteration.

Indeed, something even stronger may be true: I'm finding that when I read any passage intently now, I'm noticing more about the text, independent of whether I plan to memorize the text or not. I suspect this is part of the reason some people are so much better than I am at memorizing text: they've learned to pay attention to texts in ways that I do not. This process is retraining me to pay attention in some of those same ways. While I think of myself as having a poor verbal memory, I do have a good memory for certain other things – (often) for mathematical and scientific ideas, for facts and figures, for the gist of a story, for people. These are all things of intense interest and enjoyment to me, and so I tend to notice a lot; I make meaning more quickly than I do with text. I think Anki has been useful as a kind of bootstrap or ratchet for generating the kind of meaningful engagement with a text that I easily find with (say) a mathematical idea.

The role of Anki: While my use of memory systems "worked", I ended up thinking that current memory systems are not quite the right tool for the job. Now, it's true that the kind of deep analysis of the passages that I did was enormously valuable, and Anki provided good training wheels to enable that. I want to durably remember why "the aggregate of our joy and suffering" is better than "the aggregate of their joy and suffering". And dozens of other similar choices. But while that's valuable, Anki presents these questions in the wrong way, stripping out the context and feeling of the entire passage.

I trialled an alternative approach, copying the passage to a Google Doc, and then gradually annotating the passage – with questions about things like the word choice of our. It was clunky, but had the enormous benefit of leaving me well connected to the overall passage. With that said: the marginal annotations got too crowded and difficult to navigate. Rather than consult the annotations I found it more useful to simply note that a word or phrase had been highlighted, and ask myself what the annotation was. I'm optimistic something in this vein could work well, but my initial Google Doc experiment wasn't quite right. I suspect the following few changes (or some variation) would help:

Alternate approaches aside, it's valuable to contrast the above Anki-assisted process with a more "normal" process of memorization. When I was asked to memorize texts in school, roughly speaking what I did was much more of steps 2, 4-6, 8 and 10 above, but much less deep analysis of the text. Conversation with others suggests that's a pretty common experience.

Concluding thoughts: It is conventional wisdom that memorizing texts is a poor use of time. If the process I've described was just about memorization, I expect I would agree. But, to reiterate, it turned out that memorization wasn't the main benefit. The main benefit was a much deeper understanding of certain beloved texts. I suspect it will improve my writing permanently. It has also made me much more aware of how I speak. It's transformative in part because I find language and writing a very unnatural form of thought; this process required much deeper analysis of (and attention to) language than I'm in the habit of applying. And so I'm glad I did this project, and I expect I will memorize more passages in the future, though sparingly.

Incidentally, the work of Helga and Tony Noice on memorization by actors and other professionals makes for interesting reading. It certainly influenced my broad point of view – especially the emphasis on gradually deepening one's understanding of authorial intent.↩︎

By this, I mean memory systems building on the idea of spaced repetition. I know some orators use memory palaces and related ideas to help memorize passages of text. I have only briefly explored that, and won't report on it in these notes. In general, I've found memory palaces much less flexible and powerful than spaced repetition systems – especially for abstract conceptual understanding – even though for certain narrow uses they seem better suited. For that reason I focus on spaced repetition and its variants.↩︎

While I don't like weasel-worded variants, there's a real tension between sharp answers and correct answers. I don't know what the soldiers of the South thought, so I am merely making a (very plausible, in my opinion) inference. In practice, I tend to err on the side of a plausible sharper answer.↩︎

This card doesn't explicitly point to the context of the Gettysburg Address. Nor did I put it in a separate Anki deck. You might wonder – I certainly wonder – if that's going to make the card seem rather strange upon future review. I experimented with tagging the cards with tags like "ga" (Gettysburg Address) and "pbd" (Pale Blue Dot), but have been inconsistent. In practice, so far I've found that I quickly recognize the context. But I don't know how well they will work in the future.↩︎

Incidentally, I talked to ChatGPT about this example, and my answer is based in part on its response.↩︎

This document of course serves some of this function, though it's not nearly as demanding as reciting a passage for an audience.↩︎