Notes by Michael Nielsen, based on a problem posed by Jonathan Blow in a Twitter update on May 26, 2014. These notes were last updated on May 29, 2014.

Problem statement

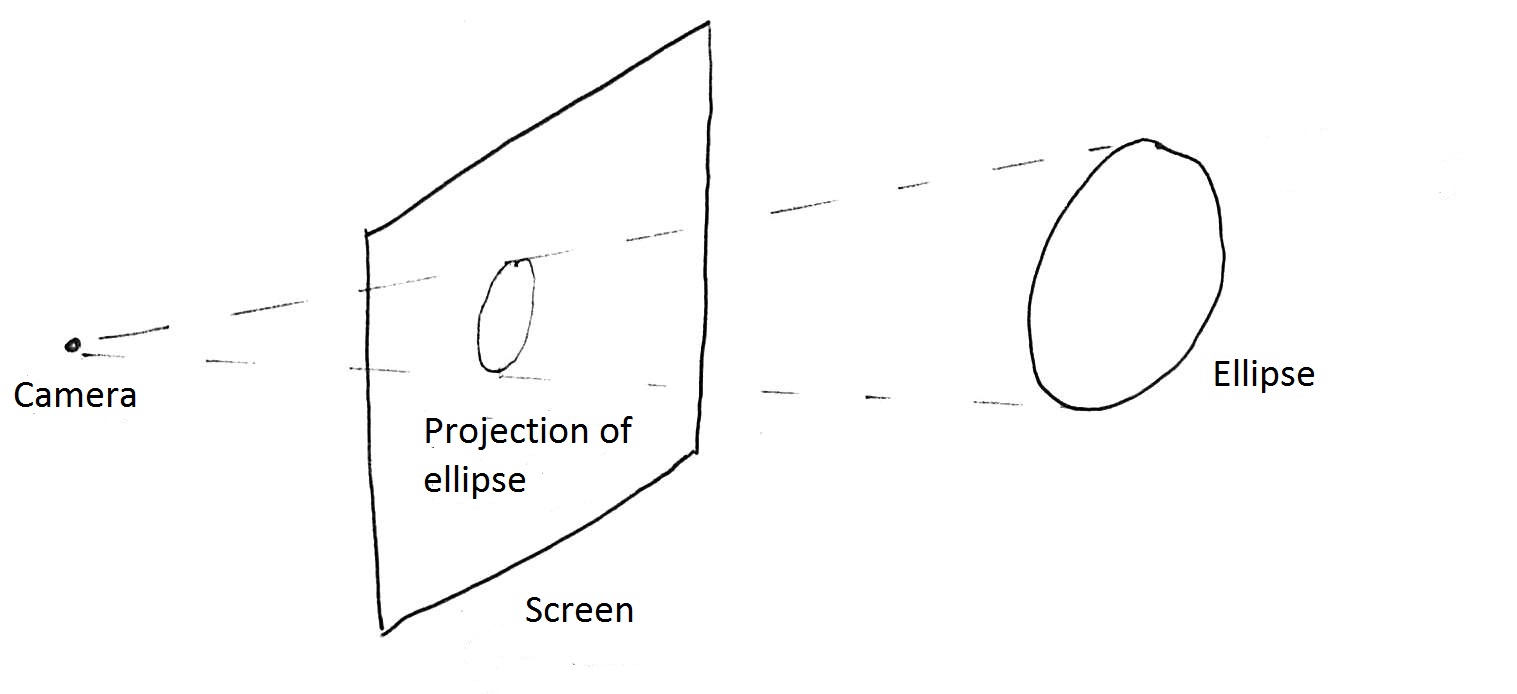

The original problem posed by Jonathan Blow: what is the area of an ellipse when projected onto a screen?

More precisely, suppose we have the following configuration:

What is the area of the projection of the ellipse, expressed in terms of data defining the original ellipse and the screen? Note that we make no special assumptions about the relationship between the screeen and the axes or placement of the ellipse, despite what my crude picture may suggest.

To attack this problem I shall first give a general integral formula that holds for the area of any planar shape when it is projected onto a screen. We will then see how this formula simplifies for the special case when the planar shape is an ellipse.

Notation and co-ordinate system

We shall use a Cartesian co-ordinate system, $(x, y, z)$.

Without loss of generality, we may assume the camera is placed at the origin, $0$.

We'll choose the orientation of the axes so the screen is defined by the equation $x = X$, for some constant $X$. That is, the screen is parallel to the $yz$-plane, but $X$ units along the $x$ axis. It will also be convenient to assume $X > 0$ (this helps get rid of some otherwise slightly annoying sign problems).

For the special case of an ellipse, let $\vec c = (c_x, c_y, c_z)$ define the center of the ellipse. Let $\vec a = (a_x, a_y, a_z)$ and $\vec b = (b_x, b_y, b_z)$ be vectors orthonormal to one another and defining the axes of the ellipse. The locus of the ellipse is then defined to be points of the form

\begin{eqnarray} \nonumber \vec c + \alpha \vec a + \beta \vec b \end{eqnarray}

where

\begin{eqnarray} \nonumber \frac{\alpha^2}{A^2} + \frac{\beta^2}{B^2} = 1, \end{eqnarray}

$A$ and $B$ are the lengths of the respective axes of the ellipse, $\alpha$ ranges over $[-A, A]$, and $\beta$ ranges over $[-B, B]$. We'll actually be most interested in the points inside this region, parameterized by $\alpha$ and $\beta$ satisfying

\begin{eqnarray} \nonumber \frac{\alpha^2}{A^2} + \frac{\beta^2}{B^2} \leq 1.\end{eqnarray}

In particular, it will help to remember that for any given $\alpha$, $\beta$ may range over $-B\sqrt{1-\alpha^2/A^2}$ to $B\sqrt{1-\alpha^2/A^2}$.

.For a general planar shape, we will let $\vec c$ be any point in the plane of the shape, and let $\vec a$ and $\vec b$ be orthonormal axes for the plane of the shape. It will be convenient to write points in the shape in the form $\vec c + \alpha \vec a + \beta \vec b$, and thus to regard the shape as being defined by some region in $\alpha\beta$ space.

Finally, it will be convenient to define $\vec n = \vec a \times \vec b$, a unit vector normal to the plane of the shape.

Answer

The area of the projected shape is given by the beautiful formula:

\begin{eqnarray} \mbox{Projected area} = X^2 |\vec n \cdot \vec c| \int \int \frac{d \alpha \, d\beta}{x^3}. \end{eqnarray}

Here, $x = x(\alpha, \beta) = c_x + \alpha a_x + \beta b_x$ is the $x$ co-ordinate, expressed in terms of the $\alpha\beta$ parameterization. The integral is over all $\alpha \beta$ parameters inside the shape.

Note also that $|\vec n \cdot \vec c|$ has a natural geometric interpretation as the product of the shortest distance from the origin to the plane of the shape with the cosine of the angle between the screen and the shape.

The formula above is not obvious, at least to me, and was obtained only after some extended work, which I won't (yet) reproduce here. I've checked the work, but it ideally should be checked by another person. If there's sufficient interest, I'll write out the proof.

The formula can sometimes be simplified substantially when the type of shape is known. We'll look below at what simplifications are possible for the special case of an ellipse.

First, thought, to build confidence in the correctness of Equation (1), we'll look at two simple cases where we know the answer in advance, and see that (1) reduces to the known answer.

Sanity check: the special case of a shape parallel to the screen

Suppose we have a shape which is parallel to the screen, and at a distance $d$. Then we expect that projecting it onto the screen will simply rescale the shape by a factor $X/d$ in both linear dimensions, and so the projected area should be a factor $X^2 / d^2$ smaller than the original area. Let's now check that this follows from Equation (1).

To do this, note first that $|\vec n \cdot \vec c|$ will just be the distance to the shape, $d$, since the shape and the screen are parallel. Furthermore, $x = d$ for all points inside the shape. So (1) becomes:

\begin{eqnarray} \nonumber \mbox{Projected area} = X^2 d \int \int \frac{d \alpha \, d\beta}{d^3}. \end{eqnarray}

$1/d^3$ is a constant, and so can be pulled outside the front of the integral. The remaining integral $\int \int d\alpha \, d\beta$ is, of course, just the original area of the shape. And so the formula becomes

\begin{eqnarray} \nonumber \mbox{Projected area} = \frac{X^2}{d^2} \times \mbox{Original area}, \end{eqnarray}

just as we expected. This gives us some confidence in the correctness of the formula (1).

Sanity check: the special case of a shape a long way beyond the screen

In the case of an object at a great distance beyond the screen, $x \approx d$ for all points in the shape, and the formula (1) becomes

\begin{eqnarray} \nonumber \mbox{Projected area} \approx \frac{X^2 \cos(\theta)}{d^2} \int \int d\alpha \, d\beta, \end{eqnarray}

where $\theta$ is the angle between the screen and the plane of the shape. Of course, the integral on the right-hand side is just the original area, and so the above becomes

\begin{eqnarray} \nonumber \mbox{Projected area} \approx \frac{X^2 \cos(\theta)}{d^2} \mbox{Original area}. \end{eqnarray}

This is also exactly what we'd expect: we do a linear rescaling of each of the original dimensions by a factor $X/d$, and do an overall correction by a factor $\cos \theta$ to account for the fact that the shape is at an angle to the screen.The case of an ellipse

For the special case of an ellipse the formula (1) for the projected area becomes

\begin{eqnarray} \nonumber X^2 |\vec n \cdot \vec c| \int_{-A}^A d\alpha \int_{-B\sqrt{1-\alpha^2/A^2}}^{B\sqrt{1-\alpha^2/B^2}} \frac{d \beta}{ (c_x + \alpha a_x + \beta b_x)^3}. \end{eqnarray}

We can do the integral over $\beta$, obtaining

\begin{eqnarray} \nonumber \frac{-X^2 |\vec n \cdot \vec c|}{2b_x } \int_{-A}^A d\alpha \left( \frac{1}{(c_x+\alpha a_x+b_xB\sqrt{1-\alpha^2/A^2})^2} - \frac{1}{(c_x+\alpha a_x-b_xB\sqrt{1-\alpha^2/A^2})^2}\right) \end{eqnarray}

With a little algebra to collect over common terms and simplify this becomes

\begin{eqnarray} \nonumber 2X^2 |\vec n \cdot \vec c| \int_{-A}^A d\alpha \frac{(c_x+\alpha a_x)B \sqrt{1-\alpha^2/A^2}}{[(c_x+\alpha a_x)^2-b_x^2 B^2(1-\alpha^2/A^2)]^2} \end{eqnarray}

Substituting $\gamma = \alpha/A$ and simplifying this becomes

\begin{eqnarray} \mbox{Projected area} = 2 X^2 AB |\vec n \cdot \vec c| \int_{-1}^1 d\gamma \frac{(c_x+\gamma a_x A)\sqrt{1-\gamma^2}}{[(c_x+\gamma a_x A)^2-b_x^2B^2(1-\gamma^2)]^2}.\end{eqnarray}

This is a simple integral expression. Unfortunately, Mathematica tells me that it has no closed form solution. One needs to be careful, of course, since Mathematica sometimes gets stuck on problems that are actually soluble, but my inclination after playing with the expression and considering other approaches is to believe that Mathematica is correct. The expression (2) likely is the best closed form expression possible.

As a sanity check on Equation (2), let's consider again the case where the ellipse is parallel to the screen. In this case, $a_x = b_x = 0$. After a little simplification the expression (2) becomes

\begin{eqnarray} \nonumber \frac{2X^2 AB}{c_x^2} \int_{-1}^1 d\gamma \sqrt{1-\gamma^2}. \end{eqnarray}

The integral on the right hand side is just $\pi/2$, and so (2) reduces in this case to $\pi AB X^2/c_x^2$. That is, it's just the area of the original ellipse, $\pi AB$, rescaled by a factor $X/c_x$ in both linear dimensions. That's exactly what we'd expect.

It's somewhat disappointing that the best closed-form expression we can get is a definite integral. If the goal is simply to compute the projected area as a one-off, then we can use a standard numerical integrator to evaluate (2). But what if we need to compute the expression many times, or very rapidly on-the-fly? In this case there are two possibilities:

1. Power-series expression: There is a sense in which it's actually possible to do the integral in (2). We simply expand the expression under the integral as a power series, i.e., as a sum over terms of the form $\gamma^m \sqrt{1-\gamma^2}$. Integrals of this form can be done exactly. By summing the first few terms in this series we will obtain an extremely accurate, extremely fast-to-compute expression for the projected area. All that's required for this to be an excellent approximation is that the ellipse be set somewhat back from the screen. It'll break down (or more terms will be required) when the ellipse is very close to the screen.

Note that I have not (yet) tried to do this power series expansion. It'd be a little tedious, albeit possible in principle. An expert in computer algebra could probably get the expression right quickly and with ease (they'd need to work a bit harder to get really solid estimates for the accuracy, though).

2. Monte-Carlo approximation: Another approach which avoids the integral is to do random sampling to estimate the size of the projected area. This is almost trivially easy. However, it will be much, much slower and not nearly as accurate as the power-series expression. Still, as a first cut it may well be the best approach. If something more time-sensitive is needed, the power-series approach could be used, and the Monte-Carlo approximation used to help in debugging.