Notes on the Dynabook

Computing as envisioned circa 1960:

"The only surviving computing system paradigm seen by MIT students and faculty was that of a very large International Business Machine in a tightly sealed Computation Center: the computer not as a tool, but as a demigod." – Wesley Clark.

Computing as envisioned in Alan

Kay's "A Personal Computer for Children

of All Ages" (1972, what I'll call “the Dynabook

paper”):

Computing as envisioned in Alan

Kay's "A Personal Computer for Children

of All Ages" (1972, what I'll call “the Dynabook

paper”):

Many of the ideas in the Dynabook paper now appear commonplace, even banal.

That's because those ideas won.

At the time, this kind of thinking was a big change in perspective from computers-as-demigods.

The Dynabook paper (and related work) was posing a fundamental new question: what might personal computing for everyone be?

By facing squarely up to this (and some related) questions, PARC invented much of the foundation for modern personal computing.

Slides by Michael Nielsen, for a small-group discussion with people from the Recurse Center, December 2015. The slides are brief, very rough and incomplete working notes on a tiny, tiny slice of work related to the Dynabook.

What we're going to do

We're going to wallow in some of the ideas around the Dynabook. Not a collection of facts, not about mastering particular technologies and systems. Rather, about powerful, generative questions and principles and intuitions.

Little point in memorizing these, or treating them as Gospel. Better to engage deeply with them, fight back with our own ideas, mash up and collide with other powerful ideas, use as a crucible for creation. I believe these ideas can, in concert with others, be developed much, much further.

As Kay puts it: The Real Computer Revolution Hasn't Happened Yet.

To that end: this is a conversation, not a monologue. Ask questions, point out connections, argue with me, Kay, and everyone else. Riff, riff, riff.

No necessity to “get through everything”. The goal is to marinate in ideas, and to distill out a changed understanding. That takes time, since many of Kay's ideas still appear radical today. The goal is certainly not to make it to some notional endpoint.

An incomplete, inaccurate and unfair timeline

This is for basic orientation. Distorted, inaccurate etc.

As We May Think, by Vannevar Bush (1945, with multiple later versions).

Augmenting human intellect, Douglas Engelbart (1962, at SRI)

Augmentation Research Center (under various names, 1963-1977, when it was sold to Tymshare). Developed the NLS. A high point was the 1968 Mother of All Demos. Funding from (amongst others) Robert Taylor.

Xerox PARC founded (1970). Robert Taylor managed the Computer Science Laboratory (and later all of PARC). Helped bring Alan Kay there, as well as members of the Augmentation Research Center.

1971: Smalltalk-71 created on a bet. Key later versions included Smalltalk-72, Smalltalk-76 and Smalltalk-80, which Xerox shipped commerically. Ancestor of modern idea of object-orientation (including notions such as encapsulation, inheritance, etc), building on Lisp and Simula.

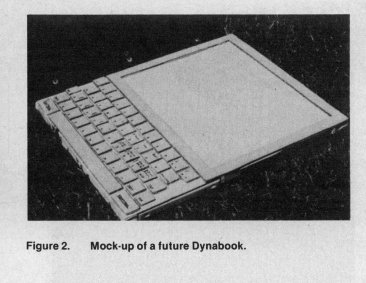

1972: Original Dynabook paper. Conceptually a precursor to Smalltalk and the Alto. Kay and collaborators revisited this several times.

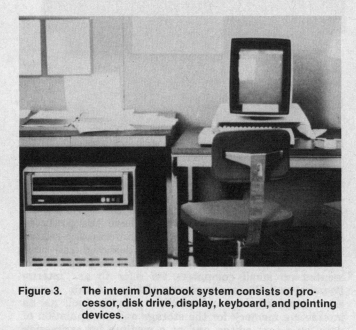

1973: Xerox Alto: mouse-driven GUI interface with windows (c.f. NLS). Designed by Butler Lampson and Chuck Thacker. Used as a substrate for the Smalltalk environment. Many iterations not just of software but of hardware too: "Interim Dynabook". Building hardware both widened and deepened thought about user interface.

The carrying capacity for discovery

Kay (2013): what is the carrying capacity for ideas of the computer?... the computer is a metamedium — it can simulate any existing media also be the basis of media that can't exist without the computer. I was particularly drawn to the idea of better childhood education with the new possibilities to represent powerful ideas that the computer brought would be a strong way to help children "grow up thinking much better than most adults do today".

This is one of the most exciting passages I've ever read.

A variant I like even more: what is the carrying capacity for discovery of a computer?

To the extent that we can reify (all) existing knowledge inside systems, it then becomes possible to play with and extend those systems.

This changes relationship we have to knowledge: Norvig; Euclid: The Game.

We stuff powerful ideas about the system into the user interface; mastering the subject then becomes (approximately) about mastering the interface. And meaningful discovery then becomes about extending the limits of the interface.

Building a model of oneself

Kay: an environment which... allows [a child] to gain a model of himself is tremendously important.

What does Kay mean to gain a model of oneself?

Possibly Kay is talking about experiences which change our self-perception:

E.g. "When I played tennis as a teenager I learnt that I enjoyed being on a team more than working solo." [or vice versa, it doesn't matter: the crucial point is a more developed understanding of self]

A more sophisticated understanding of self may be: "I have the following skills / preferences / values, and that helps me get more out of being on a team than being solo."

To what extent does this matter? Why does it matter or not matter? Does it matter for all people, not just children?

Building a model of oneself

To what extent does existing software help people develop a model of themselves?

"I'm a Wikipedian." "I'm a blogger." "I'm a designer who uses Illustrator." "I'm a [insert identity]." These are sometimes strongly associated with developing specific traits that people are aware of having, and which they have theories about.

Flipside: certain business models rely on short-term user engagement, but have negative effects on the user's long-term welfare. The result may be self-loathing, an alienation from and diminished model of self.

Are we building tools? Or media?

A distinction implicit in much of Kay's discussion is between building tools versus building a medium. For instance:

What then is a personal computer? One would hope that it would be both a medium for containing and expressing arbitrary symbolic notions, and also a collection of useful tools for manipulating these structures, with ways to add new tools to the repertoire.

There's a useful distinction here.

Tools solve very specific problems.

Cut-and-paste is a tool. The lassoo is a tool. Even something like changing the font size is a tool.

A medium, by contrast, is a platform for some broad class of creative expression. You can imagine carrying out a meaningful creative project within such a medium.

Photoshop is a medium. Microsoft Word is a medium. The web browser is a medium.

The distinguishing question seems to be: can you imagine using this program to build a significant creative project? If yes, it's a medium. If no, it's a tool.

Tools often have specific inputs which map to specific outputs. But media typically have generic inputs which are transformed by the user to imagined outputs.

Tools are tremendously important. But media are the overall environment we use to think and create. And so, to me, they hold more overall interest.

Verbs and nouns

Kay: "We feel that a child is a “verb” rather than a “noun”"

This point of view is in opposition to the point of view taken by educators (or by traditional media).

We “educate” people, that is, education is something which someone well-informed “does to” someone who is ignorant. Those people are passive receptors, things that are operated on by teachers.

Another point of view is that people educate themselves. The most anyone can do is create enabling circumstances.

Even without taking a point of view on this, an interesting thing about personal computers is that they can provide a structured, responsive environment for individual exploration. That's difficult in traditional classrooms. And so it creates an interesting possibility.

In a way, Kay's "carrying capacity for ideas" has a slight nounish flavour. "Carrying capacity for discovery" is perhaps more fully verbed.

Key Sources

A Personal Computer for Children of All Ages (Kay, 1972)

Personal Computing (Kay, 1975)

Microelectronics and the Personal Computer (Kay, 1977)

personal dynamic media (Kay and Goldberg, 1977)

Computers, Networks and Education (Kay, 1991)

The Early History of Smalltalk (Kay, 1993)

The Real Computer Revolution Hasn't Happened Yet (Kay, 2007)

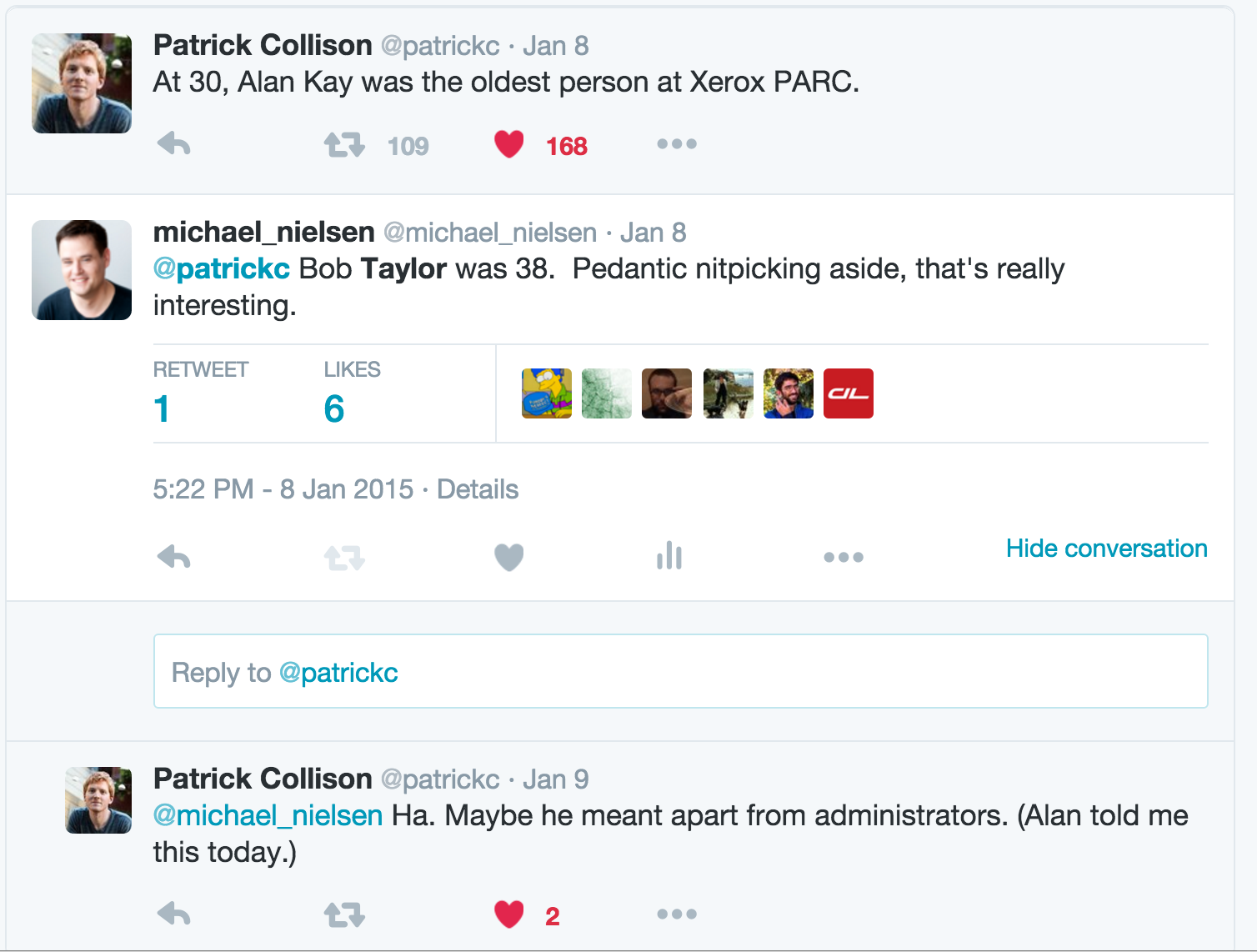

An interesting observation:

I'm unsurprisingly unkeen on an ageist interpretation.

Kay: For most of recorded history the interactions of humans with their media have been primarily nonconversational and passive... A mathematical formulation-which may symbolize the essence of an entire universe-once put down on paper, remains static and requires the reader to expand its possibilities.

Consider E = mc2.

These are Unicode characters.

On paper, characters are lifeless entities. We've copied that.

/